ProductenStoelenLoungestoelenSofa'sBureaustoelenChaises longuesKrukken en bankenSculpturenVergader-/bezoekerstoelZitmeubels voor luchthavensBergruimteMicro architectureEettafelsCafétafelsKoffie- en bijzettafelsBureausKantoormeubelsystemenVergadersystemenVerlichtingKlokkenDecoratieve objectenKapstokken & wandrekkenSchalen en vazenNieuwBestsellerSnel beschikbaarKleuren & materialenAlexander Girard Antonio CitterioBarber OsgerbyCharles & Ray Eames George NelsonHella JongeriusIsamu NoguchiLounge chair finderOffice chair finderGift finderOnderhoud & reparatieReserveonderdelenOnderhoudsproductenFabrieksgarantieprogrammaVitra Circle StoresVitra Circle for Contract (Zakelijke klanten)Gratis upgrade voor uw Eames Lounge ChairHang it allInspiratiesWoonkamerEetkamerThuiskantoorKinderkamerOutdoorHome StoriesAugmented RealityKleuren & materialenHome SelectionWerkplekkenFocusMeetingWorkshopClub OfficeCitizen OfficeStudio OfficeDynamic SpacesReceptieruimteLuchthavensOnderwijsCo-WorkingHealthcareOnze klantenDestination WorkplaceKlassiekers, een klasse apartBureaustoelenDancing OfficeHome StoriesDe Home Selection stoffen van Kvadrat en DedarAugmented Reality - breng Vitra-producten bij je thuisSchool of Design: Toon werk en kennisKlassiekers, een klasse apartKleuren & materialenEen uitnodigend huisEen kantoorlandschap - zonder muren of scheidingswandenComfort & duurzaamheid gecombineerdEen toonaangevende ruimte voor een toonaangevende kunstacademieDienstenOnderhoud & reparatieReserveonderdelenOnderhoudsproductenFabrieksgarantieprogrammaFAQ en contactHandleidingenConsulting & Planning StudioVitra Circle StoresVitra Circle for Contract (Zakelijke klanten)Advies & planning in het VitraHausHandleidingenOnderhoudsinstructies voor buitenReparatie, onderhoud, revisie op de Vitra Circle Store Campus ProfessionalsCAD-gegevensProduct Data SheetsCertificatenDuurzaamheidsverslagHandleidingenMilieu-informatiepConPlanningsvoorbeeldenColour & Material LibraryCertificaten en normenHome SelectionNaar de dealer loginOnze klantenMyntDestination Workplace: Bezoek onze klanten en partners.Anagram SofaMikadoTyde 2 op wieltjesACXDancing OfficeBureaustoelenMagazineVerhalenGesprekkenTentoonstellingenOntwerpersProject VitraDoshi RetreatCatwalk: The Art of the Fashion ShowA Capsule in TimeSeeing the forest for the treesRefining a classicMynt is a lifetime achievement to meA desk like a typefaceV-FoamSculptural IconsGames bring people together – just like good officesLet there be light!Social SeatingJust Do It!EVER GREENWhy the Eames La Fonda Chair was designedWhen a Sofa is more than just a Sofa: Anagram100% virgin wool – 100% recyclableAn archive is like a time capsuleVitraHaus Loft - A conversation with Sabine MarcelisA 1000 m2 piece of furnitureThe Eames Collection at the Vitra Design MuseumAbout the partnership between Eames and VitraVitra CampusExpositiesRondleidingen en workshopsGastronomieShoppingGezinsactiviteitenArchitectuurUw evenementAdvies & planning in het VitraHausPlan je bezoekVitra Campus appCampus EventsNieuwsDoshi RetreatVitraHausVitra Design MuseumVitra SchaudepotVitra Circle Store CampusOudolf GartenOver VitraDuurzaamheidJobs & CareersOntwerpprocesHet origineel komt van VitraGeschiedenis - Project Vitra

The Maison Jean Prouvé

An interview with Catherine Prouvé

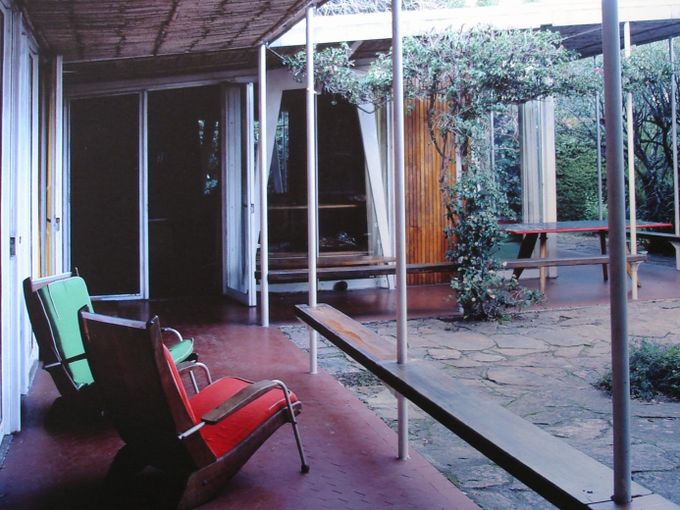

The Maison Prouvé is among the houses that have defined twentieth-century architecture. It was designed by Jean Prouvé for his family in 1954 and assembled mainly out of standard factory components constructed in the workshop of Ateliers Jean Prouvé.

The family’s home was built on a larger wooded hillside that Jean Prouvé and his wife, Madeleine, had acquired overlooking Nancy, their home city in the Grand Est region of France. The couple’s youngest daughter, Catherine Prouvé, who turned 14 that same year, warmly recalls the lively springtime when the house was built, especially the successful execution over the weekends that included both family, friends and employees from the Ateliers Jean Prouvé.

Catherine Prouvé: My mother had wished for her own house for several years, but when the time finally came it all went rather fast. With the help of family, friends and colleagues, our future family home was built in only a few months. The house was mostly assembled with ‘leftover standard elements’ from my father’s former workshop, the Ateliers Jean Prouvé. It was a happy time in many ways, but for my father who just had abandoned his workshop, it was also a very difficult period.

Why did your father leave his workshop?

CP: My father established his first metal workshop in Nancy in the mid-1920s and later a second one that moved to larger premises. In 1947 he established a big factory a few kilometres to the north in Maxéville. Maxéville was a ‘pilot plant’ where the architects, workmen and foremen were associates. The architects were based in the factory too, working as one team. In my father’s factory, a congenial atmosphere had developed over the decades, which fostered mutual respect and not least innovation. There was a mutual understanding among the different disciplines and free and unfettered collaboration between the creative workers and those who executed their ideas. This situation created a rivalry which never went beyond the bounds of friendly competition, but it established a growing reputation for originality and quality in connection with the Ateliers Jean Prouvé.In 1953 Aluminium Français had become the major shareholder of my father’s company but, unfortunately, the new investors did not understand the spirit of the creations, or the efficient methods applied in the workshops. Instead, they had observed a ‘style’ that made commercial sense for various types of architecture and wanted to segregate the people working at the factory. In June 1953, Jean Prouvé finally abandoned everything he had created, as it was no longer possible to continue the interdisciplinary method that he had developed and so deeply believed in. My father said: ‘Innovation is a group affair… In life you do nothing alone. Work is a collective venture.’ At that time my father’s friend, Le Corbusier, said to him: ‘They have felled your timber, make do with what’s left.’

So, while building his house, he no longer had access to the Ateliers Jean Prouvé?

CP: Correct. The house was therefore mainly built out of ‘leftovers’ and for the few additional components he had to order the goods like every other client of Ateliers Jean Prouvé. The house is great evidence of how my father was able to get the most out of the least. Despite the difficult conditions, our home immediately gained recognition among architects and designers and was soon highlighted in a range of French and international reviews for its comfort, economy and flexibility.My father once said, ‘The house of my dreams is made in a factory’, wanting to industrialise housing by using prefabricated components. At that time, while we built our family home, he had already designed and built several versions of demountable houses – now it was time to build one for himself.

Please explain the construction of the house.

CP: The construction period extended from 1953 to the summer of 1954. The first stage was to do the groundwork, as the base had to be dug into the side of the hill. My father had started to work from Paris and was only home at the weekends to work on the house – but we soon saw that old companions from the factory would turn up on Sundays to support their former boss. It was a demonstration of friendship. They threw off their jackets and rolled up their sleeves to help with the construction.In the family, we all had our specific responsibilities. My parents had a 4-wheel-drive American Jeep, and this was used by my brother to transport the pieces to the top of the plot. My cousin brought up the panels, and my mother served drinks. My role was to sort bolts and to keep the site tidy. After the weekends, when I came back to school and my friends could tell stories about their adventures, hikes or trips, all I could say was that I arranged bolts and screws for our new house [Catherine laughs].

A three-week run in May and June enabled the completion of the outer envelope of the house, and before the house had running water and before the internal partitions had been installed, we moved in. My mother did not have much patience, plus we had to leave our former home, a small apartment in Nancy. The first nights spent in the house were in a wide open space with no individual rooms.

How was it to live in the house?

CP: It was the first time I had my own room, so I was definitely happy. The entire house is constructed with modules measuring one metre by one metre, and my room was exactly three by two metres. The small size was ideal for a child’s room. The furniture was carefully designed by my father, comprising a standard single bed, a desk, a chair and a wall shelf. My wardrobe was part of a twenty-seven metre long system designed to contain the storage for the whole family, while at the same time acting as insulation towards the north-facing back wall. My father had thought of a place for everything. We even had a small phone booth in that storage wall.The different parts of the house have different widths, whereas the living room, facing south, is the largest space.

My father called it the ‘auberge’. This space was essential to my father because we were a very sociable family and often had guests. It was here that we spent the most of our time. In the living room, my father installed a big loudspeaker. He loved to listen to music and especially Bach. He often turned up the volume to make the music louder, and my mom turned it down again. I liked to listen to rock-and-roll and dance around the pole in the middle of the ‘auberge’, connected to the roof of the house.

Most of the material used was steel, wood and a little aluminium. The walls were made out of wood and the frameless bedroom doors simply sawn out with rounded corners – like in a ship. These details provided a very cosy and soft feeling to the interior.

Along the back wall in the living room, my father designed a flexible shelving system integrated in the steel sections of the house, a combination of white-painted bent metal shelves and blue-painted elements, wooden parts and dimpled metal cabinet doors.

Along the back wall in the living room, my father designed a flexible shelving system integrated in the steel sections of the house, a combination of white-painted bent metal shelves and blue-painted elements, wooden parts and dimpled metal cabinet doors.

Towards the kitchen in the living room, my father left a space for a small open slab of earth. The date palm that you see there today is from when we once threw date seeds into it. One day a tree sprouted up from these seeds – and we decided to let it grow. It grew quite big and we had to cut it several times – it is part of the house’s history now.

How long did you live in the Maison Prouvé?

CP: I lived here until I turned 18 and went to the United States for a year with an American Field Service scholarship from the Plan Marchal. When I came back, I lived here for a short while but soon moved to Paris to study art history.My father died in 1984. After our mother’s death, none of us children wanted to move back to the house in Nancy. Our father was very famous in the city, and we wanted to continue our own independent lives and not be constantly recognised in the streets. We therefore sold the house to the city of Nancy, and it is today maintained by the Musée des Beaux-Arts and open for guided tours every Saturday during the summer.

It is a pleasure and delight to see how the house can still serve as an inspiration for new generations.

Publication date: 25.08.2022

Author: Stine Liv Buur

Image: 1-2+4-8: 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich, Photo: Dejan Jovanovic; 2: Vitra; 9: Jean Prouvé in the living room of his house in Nancy, France © ADAGP © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Fonds Prouvé; 10: Simone Prouvé, third child of Jean Prouvé reading in front of the house in Nancy, France © ADAGP, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Fonds Prouvé. Photo : Jean Prouvé; 11-13: Vitra;